Tenement Way of Life by Yuko Tanaka

Many parents for many children

Who first said a child needs its own room?

With your feet thrust under the kotatsu, fighting with your elder brother every few minutes, you still managed to wield your pencil with skill and do your home work.

"I am beat," you would cry, then flop down or flick on the TV or pick up a comic book. Whatever you did was done under the eyes of Mom and Dad and Brother and Sis. Selfhood developed in a natural way in view of others. Others did not watch you as much as their gaze acknowledged your existence in return for your acknowledging theirs. From this mutual recognition came selfhood.

Privacy is necessary in a society where surveillance, betrayal, and yellow journalism are commonplace. But another's eye is not always an evil eye. It was certainly not so in the case of the family. Yet we have cut ourselves off from others with the result that we have lost sight of ourselves.

More and More Japanese are leading isolated lives and doing just as they please or, at the opposite extreme, so toeing the line that they fall ill. People normally exist at neither extreme; rather they make subtle adjustments, shifting back and forth across the middle ground.

People who do that well and bring happiness to themselves and others are called "adults" or are said to be "nice people." Children reared by adult parents don't need their own rooms.

The degree of intimacy between family members without their own rooms resembles that between families in a tenement house.

Whenever I hummed in front of the sink in the kitchen of the Yokohama back street tenement house where I was born and raised, someone on the opposite side of the wall, that is, a next-door neighbor, would say, "Ah, Yuko-chan, you're helping with the housework today." If it had been a tenement house in the Edo period, there would have been no cabinets, television, or curtains. There would not even have been closets. You would have been heard next door if you would hummed in the center of the room let alone in the kitchen. You wouldn't have been sure whether you where living there or elsewhere.

Keys were unnecessary in a tenement. Come summer and the door to our apartment was always wide open. There was, after all, nothing a thief would want to take off our hands. Ditto the other apartments. In many families both parents worked, and if mother and father were late coming home and the kids were hungry, they would eat at a neighbor's. Neighbors knew if they should be late their kids likewise would be fed by someone else. I still remember being scolded as I would have been by my own parents for breaking a rice bowl during dinner at a neighbor's.

In that world it was possible for a child to bond with anyone in a child-parent relationship. In the Edo Period -- no, right up to the Pacific War -- it was common to farm out a child with someone, and people who had parents beside their natural ones were not rate.

More than thirty years have passed since I spent lazy, fun-filled days in that world. When I look back now, that life-style does not strike me as having been oppressive because there was no privacy.

The separation and immuring of the individual severed the family from its surroundings and shut it up. Now things are terribly inconvenient. Take, for example, a word coined two decades after the war, in the 1960s -- kagikko, "latchkey kid."

Parents were as hardworking in the 1960s as they were before the war. Still, the image of a child with a key is pitiful somehow. It isn't pitiful because the child's mother worked outside the home. Since long ago women everywhere have held jobs and still done housework.

It's pitiful because the child returns to a home with a bolted door, and must bolt the door again after he or she steps inside. It is pitiful because the child is cut off from the outside world and has no parents other than its natural ones. If the child lived in the country, there would be grandparents, aunts and uncles, neighbors, and siblings.

In tenement houses every child had vicarious parents, and children were always visiting their playmates in other apartments. Redolent with the atmosphere of the tenement house are the conversations of patrons in the public baths and barbershops in the Low City, the low lying areas of eastern Edo, as depicted in Shikitei Sanba's Ukiyoburo ("The Bathhouse of the floating World;1809) and Ukiyodoko"("The Barbershop of the Floating World";1811).

For example, in my favorite scene in Ukiyoburo, children smeared with India ink during a penmanship lesson at a temple school drop by a public bath on their way home. Little rascals, smart-aleck brats, theater-loving kids, prim and proper little men and women -- their individual characters emerge as they trade quips as fast as ricocheting billiard balls.

The individuality of the children was revealed not only by their speech but in the subtle modulation of tone according to their interlocutor. "Let's play that shell game after we get out of the bath." "Bug off." "Spoilsport! Suit yourself, but don't expect me to lay with you ever again." "I don't give a hoot. I'm going to play theater with Kin-san and Ko-san."

If there were conversations like that, there were also ones like this:

"Tetsu-san, here, this is for you." "Ko-san, thank you. This is nice. It's a picture by Toyokuni. What a cool actor!"

Adds Sanba by way of explanation, "A boy unconsciously knew to speak differently to a well-behaved friend. " Children demonstrated subtle differences in behavior depending on the relationship with their fellows in the public bath, temple school, and tenement house.

However, when I was a child, I did not stop at a because with friends on the way home from school. In the scene in Ukiyoburo the kids, who had become covered with India ink while skylarking in the temple school, felt compelled to get cleaned up before returning home. They knew how to avoid a scolding; it wasn't always necessary for adults to make sure kids were clean.

But if the children got too rambunctious in the bathhouse and the attendant scolded them, they would tease,@"Oh boy, there goes the bath attendant again, " and resume their horseplay.

In the same way children associated with one another in the tenement house. They would be scolded by others' parents as they would have been by their own. Then they would chaff the adults. It was that sort of relationship.

Today's latchkey kids don't raise a ruckus in the public bath, are not scolded by the adult patrons, and don't raise a ruckus in the public bath, are not scolded by the adult patrons, and don't respond with banter. The reason is that a locked door separates the house-hold from the outside world. For some reason a growing number of today's Japanese feel secure behind a locked door and are happy with the thought that isolation is urban chic.

The isolation of the household has resulted in the disappearance of people who free of charge or for a small souvenir would look after a child as if it were their own while its mother was away at work. This is perhaps due to the uniformization of behavior that results from the trend toward people taking part-time jobs. A further reason is the clear-as-day distinction between "my children" and "others' children," between "my parents" and "others' parents," between "me" and "you." If your children misbehave and scrape a knee or elbow, you need only scold them, then condole with them their pain. But if you as much as scratch someone else's child, you may be sued. Such is the troublesome society we live in today. Yet there are without doubt people who think this society is advanced and good.

Children used to regard the bathhouse attendant, the barber, and woman in the next-door apartment as their parents. Today's children think of the woman next door as a stranger, for they are told over and over again to beware of strangers.

When society reaches this state, there appear professionals to care for those with special needs. Professionals receive money. No longer does the community generously embrace the children with moderate solicitude and raise them as it sees fit. Now there are "people who leave a child in another 's care "and "people who assume temporary care of a child ,"employers "and "the employed. "So money buys responsibility. If something should happen, the person entrusted with the child may be sued; she or he is also on tenterhooks.

In general, a society based solely on the exchange of money is a society that is uptight and barters in responsibility. Some people think this sort of society is good.

From volunteer movements to a volunteer society

The word "volunteer "points to a new sort of human relationship born amidst the money-for-labor exchange that characterizes society after the collapse of the community of mutually assisting people.

Although it is no longer true today, people first thought of volunteers as members of an ad hoc public organization assisting with a project. Behind such thinking was the conception of an ideal society in which government did everything necessary. Nowadays, however, it is coming to be accepted that public agencies and their bureaucrats, even when spending tax money judiciously, are never trustworthy, especially in times of emergency.

If that's the case, then "volunteer "takes on a new meaning. Volunteers were supposed to assist with undertakings by the national and local governments, and to the have become unnecessary with the evolution of the ideal welfare state. But just the opposite has occurred. People now think that the social structure should transmute into a voluntary system. Some people foresee the possibility of society evolving into a network of human relations where people voluntarily undertake various sorts of jobs for others.

In earlier times there were many sorts of relationships without an exchange of money. If money did change hands, it was not for the purchase of fixed-price commodities, but rather charity, a loan, or a gift. Otherwise it was a small token of appreciation for a favor. In relationships based on cooperation or fellow feeling rather than money, even if money were given, it was given voluntarily.

The fixing of prices for goods, and even services, represented a great convenience. But it was too convenient, for it discouraged thought.

The popularity of the word "volunteer "is indicative of the disappearance of voluntarism from the social structure. Since all relations are either money-based relations or relations involving bureaucrats and their tax-supported initiatives, volunteers have had to fill in the gaps.

Perhaps these volunteers will create a new voluntarism-based social system.

That thought brings Edo to mind.

Places neither public nor private

In Edo Period society there was nothing special about voluntarism. It was the warp and the woof of society. It was an actual system, the workings of which were visible.

Think, if you will, of potted plants along streets. When the Japanese came to desire their own houses, it meant that they would not only live in the houses, but that they would possess their own gardens. In other words, the plants and flowers which had been enjoyed by passersby and beautified the cityscape were now enclosed for the house owners' exclusive pleasure.

Even a moment's thought will make you realize that the pleasure of a garden need not lie in possession. To which someone might retort,"We have parks for the public display of plants and flowers. "That reply marks the limits of our conception today. Space, time, human relations, service -- we can only conceive of them as "things belonging to me "or"things belonging to the public. "

But the potted trees and flowers set along alleys between tenement houses and along streets in the Low City were not for private viewing nor were they within a park. The represented a middle ground, a voluntaristic space, between public and private -- a space that was at once public and private.

I'm told that in Japan, public and private are distinct spheres, but in the West, the private sphere is part of the public sphere, for which reason Westerners believe the public sphere should be expanded and the private sphere contracted.

In a certain Spanish city private gardens are open to even tourists in order to beautify the cityscape, and the government even holds a garden contest to instill pride in individuals. These are certainly examples of turning the private into the public. But it would never cross the mind of a Japanese couple who purchases a home today to open to tourists the "closed "garden they obtained at long last.

The question of a public versus a private garden is of little import, but the European view of enlarging the public sphere embraces such things as business methods and unclear testing.

When I consider the tenement house as a model society, he first thing which springs to mind is a comparison of Tao Yuan Jing and Utopia. *Many people regard the former and the latter as very similar Chinese and English versions of ideal societies. However, Tao Yuan Jing suggests a tranquil farming village where no one gives a receives orders, which Utopia brings to mind a society where a bugle calls people to assemble for a free meal. They are societies without similarities and different in nature.

So which is the tenement house? It is Tao Yuan Jing, of course. In contrast, Utopia corresponds to an advanced welfare state.

I dislike the expression "advanced welfare state." "Advanced, ""welfare ,"and"state "are words reeking of a gloomy artificiality. These three repugnant words spell Utopia. My dislike of them is not only emotional. The advanced welfare state is nothing more than a political slogan and is far from realization.

For example, I heard of a couple employed by a local government who saw one of their incomes nearly consumed by the cost of day care and baby-sitters. If that's the case, then the couple would be better off if one of them stayed home and cared for the children.

Until not too long ago the pundits said that if the Japan established free day-care centers like those in socialist states, the problem would be solved. But nowadays the common wisdom everywhere is that to do such a thing would cost a fortune and increase budget deficits.

However, if Tao Yuan Jing, the ideal of the tenement house, were used in a broad sense to mean"society, "it would be a governmentless society that foremost emphasized the joy of living.

Simply put, Utopia is nothing more than a highly controlled society.

I said earlier that these two images of society exactly coincide with the public-private dialectic. In other words, because the "private "is part of the "public "in Western pattern, the "private "must be thoroughly controlled in order to establish the abstract conception of the public good --the good of all.

Otherwise the "private "will expand to where it threatens the good of the "public ."That is why Utopia must take the form of a controlled society --the former Soviet model of the socialist state.

In the Japanese model of the public-private dichotomy the "public "and "private "are separate. They are not only separate but they belong to different orders. There is the expression watakusi suru, which means "to judge and to sway the "public "from an individualistic, biased, shallow viewpoint."

Which is the one thing an East Asian is not supposed to do.

Then just what is the "public "? Is it the emperor? No, because the emperor must guard himself against thinking of only his own gain. Was it the shogun? No, because the shogun had to do likewise. Then where is the "public "? It's nowhere. Does it resemble a frightful group consciousness that subsumes individuals' opinions?

If we compare Tao Yuan Jing to the tenement house, we see the soul of the people who lived there. Their sentiments are captured by the Edo Period expression , bun wo mamoru,"keep to one's sphere in life. "To do so was to know oneself. The inhabitants of Tao Yuan Jing can live in tranquility without external laws and politics. For they each inwardly possess an admonition against thinking of their own gain, and are keeping to their sphere in life.

No one in Tao Yuan Jing thinks of the collective happiness. There is no mechanism or organization for its achievement. If all achieve the happiness of their choice, public order will be maintained. The reason is that happiness is not making oneself "public ,"expanding the "private ,"or asserting the self; it is nothing but self-knowledge.

Sphere also suggests a spatial image. It corresponds to the "segregation of niches"in nature. The inhabitants of Tao Yuan Jing had no use for the sort of persons whose growing ambition leads him to run roughshod over others.

The tenement house was not Tao Yuan Jing, nor would we have expected it to have been. But if we posit an ideal state of the tenement house, it is not Utopia but rather Tao Yuan Jing.

Happiness in a 2.7-by-3.6-meter apartment

Having described human relationships in the tenement, the image of the tenement, and psychological state of tenement dwellers, I would like to turn to tenement life in the Edo period.

The average apartment in a tenement house had a frontage of 2.7meters and a depth of 3.6 to 5.4meters. If the dirt-floor vestibule is expected, the apartment was something like a 4.5-or 6-mat room. Many apartments had second-stories that were reached not by stairs but by a ladder through a hole in the floor. The second story must have been snug.

Regarding the apartment's floor space, I read in an encyclopedia that "Edo Period tenements were cramped because households averaged four members. "I was left with the impression that the writer of the article had been born with a silver spoon in his mouth. My family of five lived in an apartment roughly the same size. The main difference was that the Edo tenement lacked the space for a closet and kitchen with elbow room. In any event, to judge someone's life-style as poor or cramped by the standard of your own is the height of arrogance.

In my case, because other children lived like me, I never thought that I was poor or that life was uncomfortable. It was not unhappy. I've met, many different kinds of people since I became an adult, and I was surprised by the number who described having grown up in circumstances similar to mine, or in apartments that were even smaller.

The values of people who like to paint as bleak a picture as possible of Edo and prewar Japan have three things in common.

The first is that happiness derives from affluence, large home--in short, it depends on quantifiable things.

The second is that human relations that involve caring for one's parents or doing things for others represent unhappiness, while independence and having everything done for one by the government and corporations is happiness.

The third is the belief in the myth of human progress.

This sense of values is responsible for the weakening of human bonds and for the obsessions with increasing one's income. One can't borrow miso or soy even if one wants to. One can no longer accept a stranger as a "whole "of which one part is unknown, but must deal with him or her through the medium of money and in terms of occupation, academic credentials, and social status.

Society grows inflexible, and unless there appears a new human network, individuals will lose spirit. Kaneko Ikuyo, the author of Volunteers, sees voluntary action as a way to discover a new network and to discover a new pleasure. He had put that view into practice by forming inter-V-net, a global network of volunteers, to assist the victims of the Great Hanshin Earthquake.

The possibility of a "global tenement house "lies in people, on the basis of scant reports only, going to the aid of, sending essentials to, or requesting help for people in faraway places. This is not a matter of money changing hands or of loss and profit or of give and take; rather it represents a new way of thinking in which information links with information and people link with people. This has been made possible by the Internet.

Kaneko, in Internet Strategies, the transcript of a conversation between him and two others, ticks off a variety of new images of "linkage. "Volunteer action no longer fills in the chinks in society; rather it has the potential to be the nucleus of a reordering of relationships by serving as a vehicle for a new global information environment.

I would like to discuss the possibility of a global tenement house with many other people.

Discussion of the Edo tenement house expanded to discussion of the global one. I'll return to the subject at hand.

I said earlier that one of the three features of people whose values lead to a negative view of the Edo Period is belief in myth of human progress. It is perhaps a belief that derives from the Western theory of the evolution of society.

Of course, the indices of progress are quantitative expansion and the refinement of technology and science.

Returning from a three-day forum I found myself seated next to the forum's sponsor, a bureaucrat in one of the ministries. He suddenly turned to me and blurted,"I hate the Edo Period." "Huh. Why's that? "I asked, my curiosity aroused. But his reason disappointed rather than surprised. "There was little population growth," he explained.

He later said that my characterization of the Edo Period was mistaken. Once again I was eager to have him elaborate. Again he didn't fail to disappoint me: "It was different from what I was taught in school."

I know some government officials with first-class minds. Not everyone in the bureaucracy is as dim-witted as my fellow train passenger. Nevertheless, the encounter reminded me of what the Japanese Government considers the best and brightest.

The theme of the forum held by his department was finding a relationship between Japan and the rest of Asia that was not foremost an economic one. He probably did not even know why he had been sent to attend the forum.

The example of this man, a graduate of a top university, shows that credentialism does not blind one as much as self-conceit does. Even if he heard something that ran counter to what he'd been taught in school, he would pay no heed, and even if he did, he would say, "You're wrong!" and with that dismissal purge the heresy from his mind.

It seems he had learned in school that the human race advances with time, and that progress is measured in terms of "increase," of, first of all, population. Even a schoolchild knows that India and China have population problems, and that the increase in world population is taxing the environment.

A moment of sober reflection will reveal what so-called progress holds for the human race.

Tenement house folk

Let me return to the Edo Period.

The tenement house consisted of ten to twelve units 4.5 to 6 tatami mats in area. For that number of units there was generally a single well. It led to an underground conduit of clean water from the Tamagawa or Kanda waterworks. Water was drawn by lowering a bucket attached to the end of a bamboo pole. Clothes were washed by the well side. Water carried from the well and stored in household jugs was used for cooking and washing dishes in the kitchen.

Edo had waterworks. To be sure, Edoites did not enjoy the convenience of water at the turn of the tap. Still, we should not underestimate the city's achievement. In the seventeenth century Edo possessed a one-hundred-and-fifty-kilometer-long network of underground conduits, and by the nineteenth century its waterworks were one of the world's largest in area and population served.

In 1800 the three largest cities in the world were London, Paris, and Edo. London had a population of 900,000 and Paris, of 600,000. New York, with 60,000 inhabitants, was not yet a great metropolis. Edo teemed with 1.2million people spread over a vast area.

The only large cities with water supplies in the seventeenth century were London and Edo. Londoners, of course, did not have the convenience of tap water either. Water was supplied by a network of aboveground wooden pipes. Paris didn't possess waterworks until the early nineteenth century.

Moreover, Edo alone supplied water twenty-four hours a day year-round. London supplied water for seven hours on three days a week. The Japanese are so accustomed to having a steady supply of water that they have a word for its interruption: dansui. But at the time London possessed the second most sophisticated waterworks in the world.

The sewer ran down the center of the alley between tenement houses. The alleys were never flooded, because rainwater and clothes-washing water drained into the sewer. Water drawn from the jug for washing dishes was poured into the sewer. The only neutral detergent was soap and there was, of course, no flush toilet. Nor was there a bath in the tenement house. So tenement sewage contained no noxious substances.

The toilet was a communal latrine. Excrement was sold as night soil. Although in the Edo Period prices were so stable that it took two centuries for wages to double, night soil, always in short supply, nearly quadrupled in price in the latter half of the eighteenth century, fomenting a movement for the reduction of its price. Although human waste was merely a filthy nuisance for tenement dwellers, it was, as a valuable commodity readily converted to cash, an important source of income for the tenement house owner.

Just as voluntarism was not a movement, but a part of the social systems, so was recycling. All human and animal excrement, trees and bamboo, cloth, goods made from natural objects, even ashes, were recycled. Garbage was also used as fertilizer. In Edo all waste materials were returned to paddies and fields.

The god of harvests was often enshrined at one end of tenement house. A village or town, regardless of size, enshrined a small image of a god as a guardian of the entire community. Though I didn't live in an Edo Period tenement complex, entered through a wooden gate, soon after passing through the alleyway there was a small shrine to the god of harvests. Until a certain age, whenever I passed that shrine, I would be gripped by fear, and stop and join my hands together.

My parents hadn't taught me to pray at the shrine. The practice was passed down in the community of children. When a group of us walked by the shrine, we would be possessed by the same emotion, and in the same fashion join our hands together and bow. This was a blue-collar neighborhood in Yokohama in the mid-'50s through the mid-'60s.

What sort of people lived in an Edo tenement house?

Of interest is a detailed illustration(facing page) of the entrance to a tenement house complex in Shikitei Sanba's "Barbershop of the Floating World, " for the wooden gate shows the tenants' nameplates. Since they also served as advertisements, they might better be described as posters or signboards.

For example, there was a sigh for a guide for pilgrimages to Mt.Mine; a tour conductor would require a signboard if he were to gather clients. Also hanging out their shingles were a marriage broker and a fortune-teller and a Confucian scholar who taught how to read Chinese texts. There were a doctor and a moxibustionist, a samisen maestro and shakuhachi master. We can presume there were carpenters and other artisans, though they did not hang out their shingles. In tenement house complexes the ratio of artisans was high, and the largest percentage were carpenters. There were also retirees and masterless samurai.

Vendors were continually passing in front of tenement houses. The illustration shows peddlers of Chinese cabbage, confections, malt, and mussels and short-necked clams. These peddlers, themselves tenants, made the rounds of surrounding tenement houses according to a nearly fixed schedule.

Fish, vegetables, tofu, natto, knickknacks, rental books, rice cakes in vegetable soup, rice-flour dumplings, a sweet drink made from fermented rice, boiled foods, rice, salt, plant and flower seedlings, tiny aquariums with Deacan grass --life's necessities from foodstuffs to hobby goods were hawked in Edo by a virtual army of peddlers. If seasonal goods were added, peddlers' wares were innumerable, for which reason tenement dwellers did not need to go shopping.

This vivid illustration also shows a big man rocking a baby, a sleeping dog, a girl with many fancy pins in her hair, a chic woman in striped kimono. The people in this illustration are perhaps tenement dwellers, but their kimonos, hair decorations, expressions, bearing, and mood do not convey poverty. In other words, they themselves don't feel they are poor.

The carefree, happy faces of the people who appear in "Barbershop "and "Bathhouse "each tell of the tenement way of life. Poverty(dire hunger and other life-threatening circumstances excepted)is a relative matter --a matter of the perception of one's own circumstances in comparison with another's.

In my childhood I didn't think I was poor. I knew there were more affluent families, but they weren't significantly better off than us. I also knew there were poorer families; I had seen them with my own eyes.

My paternal grandfather had died while my father was still a boy, leaving my grandmother to support five children on a seamstress's income. My father couldn't, of course, go to middle school or high school. My father has since passed away, but whenever my aunts and uncles talk about their childhood, I've felt the affection and strong bonds that united them as children, and have envied their freedom and their having been left to themselves.

I imagine that life in an Edo tenement house was the same.

In the crowded tenements people lived while searching for the best way to coexist with others. One's downfall lay in over accommodation to family members or society, or in excessive meddling in others' affairs.

In Tao Yuan Jing, even though people were on the same wavelength, they did not unite for, say, war or team sports: There was no competition to win. Perhaps we have lost the knack of bonding without uniting, of perceiving when our assistance is necessary but not officious, of knowing how to accept help without becoming dependent on others.

I can almost hear the skeptics dismissing such speculation as so much recalling of a golden age that never existed. Let me quote a passage Ishikawa Tadao, the president of Keio University, wrote about his neighborhood in Kanda Hitotsubashi, Tokyo, in the early 1930s:

"Houses huddled together in Hitotsubashi. Neighbors got along, and evenings everyone would exchange side dishes as people in the Low City of Edo had borrowed miso and soy sauce. People liked helping others, and if asked to do something, would comply without complaint, though they would never meddle in another's affairs. That was perhaps a rule of living nose-to-nose in the Low City of Old Edo."

The knack of bonding is a requisite condition for building a society on the basis of voluntarism. Let me add that this pertains not only to relations between humans: we must also possess the knack of bonding with other species, with things, and with language. This knack is evident in the method of linking renga and haikai verse.

If, then, Edo tenement dwellers possessed something we've lost, we have no reason at all to pity them, nor do we have a single reason to believe we're living in an age that is blessed because of "progress."

What we're doing is getting ulcers from worrying about repaying the loan on the house with a garden.

Now we've seen that a tenement houses is a congeries of people from different walks of life. We can imagine that they physician, carpenter, and costermonger in a tenement complex were regular customers of one another.

In my neighborhood, shops faced an alley in back. This meant that shops were integral with people's lives. For example, our apartment was directly opposite the rear entrance to a long-established miso and soy shop. Everyone who lived along the alley would enter the shop through the back door. Errands took me there countless times.

The rear entrance was a strange place, a dark tunnel with an earthen floor where miso and soy fermented in barrels and emitted a vinegary odor. The shop was also our important connection with the outside; for a long time it was the sole place with a telephone. It evolved into an agency for calling people the to the phone.

From today's perspective, it must certainly appear a troublesome arrangement. But it was an arrangement in which money did not change hands. In lieu of money Mother would bring the shopkeeper confections or some other small thing when the opportunity arose. I assume that transactions in the tenement house were fundamentally the same.

Among the other establishments with back doors opening onto the alley were a croquette shop, Chinese restaurant, ophthalmologist's, and boiled bean shop.

Some people are under the misconception that a tenement complex was a ghetto. But unlike a ghetto, where the lowest strata of society live, an Edo tenement house teemed with people of all different ages and vocations. In the rakugo comic story entitled "The Three-Apartment Tenement" a chief fireman, fencing master, and concubine with tortoiseshell cat are all neighbors.

Most people associate a high population density with cramped, uncomfortable living conditions. Jane Jacobs, a polemicist poles apart in thinking from Le Corbusier(1887-1965), claimed that urban revitalization depended on four principles, one of which was a high population density. The intermingling of people in close quarters is a condition for a safe city with cultural amenities.

On the one hand, dealing with other people is troublesome. On the other hand, the close-knit intermingling of people is certainly conducive to safety. Where do more robberies occur -- in the busting city center or on the city outskirts? Interacting with others is sometimes bothersome, but it also uplifts spiritually, and culture infused with subtle shifts in human relations is of a high quality.

Jacobs's three other conditions for urban revitalization were narrow winding streets, numerous old buildings, and the absence of zoning.

These conditions suggest a tenement house complex.

Because Edo was built by legions of carpenters and other artisan migrants, there appeared quarters segregated by occupation. These quarters slowly integrated. By the time the tenement house became the standard abode, it was a department store of occupations. So the unzoned city rose.

In Hiraga Gennai's Nenashi Gusa ("Rootless Weeds ";1763)shrimp and freshwater clams recount what they witness while they are hawked in back-street tenements in Edo. Following are some of the things they see:

* A winsome young woman tries to get the hawker to sell her fifiteen-mon worth of clams for five mon. A violent argument ensues. The young woman calls the man a "whining bastard," and the clams are shocked by her billingsgate.

* There is daughter of parents of modest means. Like many young women of her class, she is taking singing lessons and learning to play the samisen. One day a go-between calls at her home and chats with her parents about an employment opportunity for her. The position: mistress of a man of station.

* A man learns of his wife's infidelity, and the couple begin flinging plates, flowers pots, and pails, then seize each other and fall to the floor and grapple.

Hiraga Gennai discovered the dynamism of Edo midst the gamut of human types jam-packed into the unzoned warren of tenements, and helped pioneer an Edo literature in which people spoke the vernacular.

One might think that chaos reigned in the jumble of tenement houses. But that was far from true. Even more so than Japanese today tenement dwellers then were independent of government and tried to solve problems themselves. And they were capable problem-solvers. In actuality, villages and towns in the Edo Period were self-reliant and surpassed today's municipalities in practical problem-solving and in independence from laws and legal safeguards.

The Edo Period town and village possessed a substantial nongovernmental unit in parallel with the governmental one. In the village, Shinto-ceremony guild, craft unions, and various mutual-help associations meshed in a complex fashion, while the town had its fire brigades, young men's associations, and mutual-help groups. The intermediaries between these groups and the government were the town headman and the "trio of village bosses"-- the headman, his clerical assistant, and the farmers' rep, watchdog over the two others.

In the town the community leaders were the fire chief, tenement landlords, and the headmen(landowners).The timber of these leaders had a direct influence on the comfort of tenement dwellers. Also influencing the quality of the tenement quarters were busybody retirees and leaders of verse-capping parties.

Vestiges of the landlord-tenant relationship are found in rakugo comic stories. The humor lies in the chaffering between the landlord and the tenant in arrears with his rent. But from this self-revealing frank exchange between two flabbergasted people arises a portrait of an intimate human relationship.

In "The Tenants' Flower-Viewing Party" the landlord summons everyone in the tenement house. The tenants, fearing they will be dunned for back rent, hesitate to go. Once they have gathered, the landlord announces that he's taking them to view the cherry blossoms."Rakuda "begins with the death of a ne'er-do-well tenement dweller nicknamed Rakuda, and the story turns on the haggling between landlord and tenants over the disposal of the body. In "A Place to Retire to" the landlord is the hapless one. He has just learned how to sing gidayu, a variation of joruri, ballads chanted to samisen accompaniment. He holds concerts, to which he invites his tenants. They think his gidayu-singing is terrible, but they dare not decline their landlord's invitation.

Like rakugo, Jippensha Ikku's Tokaido Hizakurige ("Traveling the Tokaido by shank's Mare")deals with the lives of the common people. In one chapter of the novel two women, whenever they meet to borrow or return soy sauce, grumble about the landlord's dunning them for the rent. They may grumble about the landlord, but when they have a problem with another tenant, they immediately seek his mediation. Even when one tenant owes another money, the plaintiff does not go to the authorities but to the landlord. Tenants endeavored to solve problems at the tenement house level.

Santo kyoden's illustrated storybook koshijima Toki ni Aizome is a fantasy about a reversal of values. In one scene tenants visit their landlord to ask a favor: "The urchins in back are tossing gold coins into our homes. Please scold them."

The scene reflects that tenants turned to their landlord when troubled by children's mischief. The landlord was a free lawyer and counselor.

Today is also an age of high population density. But there is no one who corresponds to the landlord-counselor or to the Low City leaders.

The tenement house and voluntarism appear unrelated. They share a common foundation, however.

Human relationships are not always relationships between helpers and the helped.(If they were, we would be a wretched society marked by yawning differences in income.) Human relationships are links between people who don't pull their punches in speaking to one another. These human links are certainly neither tidy nor tranquil. Even though we may want them to appear neat and tidy, a society where lawyers and courts necessarily come between people is a society with a high degree of tension.

I want to live in Tao Yuan Jing.

But such a place does not await us somewhere; rather, it is an image that exists in our souls. Manifesting that image is the job of each of us.

Tao Yuan Jing is a society of moderation. It is a society where people are attuned to and accepting of one another -- a society of nice adjustments. It is enough to find the right balance while speaking your mind and complaining. The society that results will not be perfect; but that matters not. If your neighbor annoys or offends, you are no the worse for the annoyance or offense. For with the irritation originates the person-to-person connection.

Tanaka Yuko is a professor of Japanese literature of Hosei University.

*Tao Yuan Jing (Togenkyo in Japanese)is the Chinese paradise, originally depicted in a novel by the poet Tao Qian(365-427).

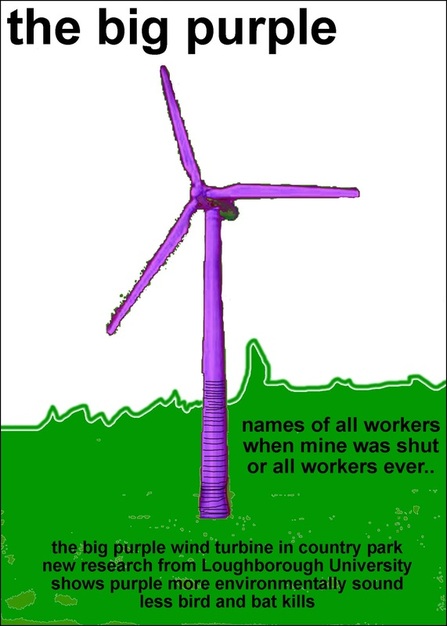

'Thus Much Liberty' is the second in the series of shamanic divination cards from 'Indifferent' by Paul Conneally. It Forms part of his wider piece for Snibston Transform - 'Spoil Heap Harvest'.

'Thus Much Liberty' is the second in the series of shamanic divination cards from 'Indifferent' by Paul Conneally. It Forms part of his wider piece for Snibston Transform - 'Spoil Heap Harvest'.